The Age of IDIoTs: Worldlines and Smartphones

21 March, 2018

category: Digital ID

By Dr. Tam Hulusi, UniKey Technologies

Over 100 years ago a physicist by the name of Hermann Minkowski postulated that all the space and time around us is one in the same; occurring simultaneously, future and past. He theorized that all objects have a resolute destination along the path of space and time – he called this the worldline. Interestingly, for a majority of us, during the typical Monday through Friday workweek, the primary and most consistent destination along our path of space and time brings us to the front door of our office building. And along our own worldline to the front door, there are a few things we do.

First off, we wake up around 6 am and go for a run, which we track on a fitness app, and pair with our favorite workout playlist on Pandora. We’ll then return home, instruct Alexa to make coffee, and hop in our cars to make our way to work. Meanwhile, we’ll avoid traffic through Waze, Siri will order a chai-to-go from the Starbucks app, that’s roughly two blocks away, or I may even drop off clothing at the dry cleaners paying by Apple Pay before arriving at the office. When the day’s work is all wrapped up we’ll jump in our cars once more, make our way home, and get ready to repeat the same actions (plus or minus some deviations) the next day.

Since most of us tend to be creatures of habit, Minkowski’s concept of a worldline – a defined path in space-time – is almost a perfect allegory to fit with our everyday lives. So how does this brief anecdote and Minkowski’s worldlines apply to smartphones and physical access control security? It’s simple.

Data In – Convenience Out

Before the arrival of the ubiquitous smartphone, access control systems heavily relied on an aggregated collection of bound data on its users in order to make logical decisions when determining who to let in and who to keep out. This bounded data set, or the data that’s completely known to a system, is generally comprised of an individual’s issued card, the time they typically request access to the building, and their access permissions throughout the premises. With the ubiquity in smartphone owners and their daily, active use of this personal technology, mobile access control may be able to add an additional layer of certainty to the authentication process of physical access control. And may provide convenience at the same time.

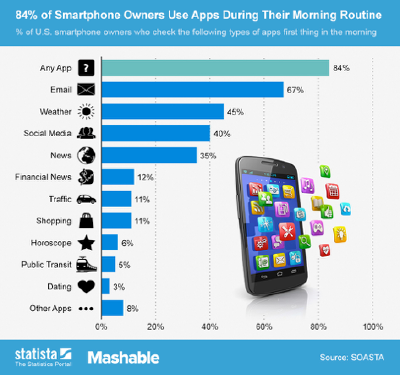

Today, the average person uses an estimation of nine apps a day, and 30 apps a month. For most smartphone owners, this evaluation comes as no surprise. The moment a vast majority of us finally hit “dismiss” instead of “snooze” on our favorite alarm clock app, a whopping 84% of us go right to checking our email, weather apps, social media, and news on our smartphones.

You’re an IDIoT !

Yet, no matter the app each of us chooses to open first-thing in the morning, we’re all doing the same thing: building a unique, digital footprint. This digital footprint, over time, develops into our very own digital signature that can effectually act as an additional layer of security for mobile access control systems – this is our own unique worldline, established over a measured and finite period of time.

Moreover, these digital worldlines have the potential to be a new form of credential. As we walk through the soup of daily activity we are constantly pinged by sensors and Internet of Things (IoT) devices. We should and could have an ID that is recognized by man or machine, simply by dint of doing what we do, each day.

These new credentials – let’s call them ID IoTs – are individualized Identifications, coupled with the tracking of location, application usage and interactive machine sensors, IDIoTs can provide a constantly updated and seamless confidence factor for more precise authentication.

My IDIoT adds a credible second or third factor to an authentication process, allowing more seamless and convenient access through a building.

Certainty in Unbounded Systems

Building unique IDIoTs, based on the use of favorite apps, say, can help a mobile access control system more confidently identify its users before they even arrive at the front door. These IDIoTs, though derived from unbounded and inherently unpredictable data, can help track the unique worldine each individual user takes throughout the workweek; helping the access control system distinguish them from other users. Moreover, through the same data set, the system can also detect anomalies, or the use of the credential by unauthorized individuals.

And, as privacy is a concern for the users, as well as the developers of this type of system, the technology would operate under the concept of differential privacy. This is a term that may sound familiar to iPhone users as Apple discussed the concept extensively at their 2016 WWDC keynote. Differential Privacy, in a nutshell, is the curation and analysis of anonymized data. As users of these products, our personal data is kept private by the addition of noise to the data while it’s being compiled in a host’s servers. This anonymized data allows companies like Apple, Google, and Microsoft the ability to unobtrusively analyze their users’ patterns and data in order to fine-tune and tailor their operating systems to their user’s needs and demands. In turn, this improves on the product’s UX and overall performance.

Similarly, IDIoTs will also use differential privacy in order to protect its users’ data and keep their digital lives anonymous. Furthermore, to maintain the privacy of users’ digital maps, users and their actions will be associated with time frames and individuals who come into the building at, or around a certain block of time.

Intentive Design

Since most access control systems rely on known data, known rules i.e. ‘active control’ from known parameters, it is difficult to tell the industry that they may be thinking the wrong way. If we have faith in the known data, then we have a system with integrity. That’s active access.

But what if all the doors were in default open mode, and only closed if the user IDIoT did not meet the threshold set the system? Firstly, it would cut down on transactions and increase throughput. It also emphasizes the concept of passive access or passive intent; lets call this a verb: INTENTIVE.

In private and at home, we see examples of intentive design. My car does not require a key to be ‘actively’ used; it’s in my pocket. I approach the car, door opens, and I can start the engine. My front door has a smart lock, I approach, touch it and it opens. These examples show that the technology is here and currently being deployed. Can we teach the industry that there are alternatives?

So, despite the access control industry’s active access mentality, Minkowski’s spacetime concepts are alive and well in our new digital reality, using digital worldines and IDIoTs, consisting of all the questions we’ve asked Alexa, all the locations we’ve navigated to with the aid of Google Maps, and all the devices our phones have connected to, have the potential to become a new derived, yet reliable credential.

About the author:

Dr. Hulusi’s distinguished international career spans both the Security and IT systems industries. He was most recently the Senior Vice President and Director responsible for corporate strategy, technology innovation and intellectual property at HID Global, a division of Assa Abloy, the leading global lock company. He was also responsible for managing a portfolio of over 900 patents and establishing and directing the corporate strategy and acquisition initiatives. He currently sits on the board of three companies, including UniKey Technologies, the world’s largest smart access control platform provider.