Feds mandate strong authentication for e-prescribing drugs

Resistance from docs, inconsistent interpretation leading to problems

28 March, 2016

category: Biometrics, Digital ID, Health, Smart Cards

The federal government requires doctors to use two-factor authentication credentials for e-prescribing controlled substances. But medical records and security experts say that the implementation of this rule isn’t quite where it should be.

There’s been some resistance from doctors, who find the requirements overwhelming. There have also been inconsistencies in the interpretations of the rules by pharmacies, the vendors of e-prescribing solutions and by the auditors that review these prescribing applications. “It’s a bit of a wild, wild west scenario out there right now in terms of how the rule is being implemented across all of these different vendors,” says Jerry Cox, director of product management for IdenTrust, which provides identity solutions and digital certificates for e-prescribing.

In 2010, the Drug Enforcement Administration issued its Electronic Prescriptions for Controlled Substances, or EPCS, interim final rule. EPCS made it legal for doctors to electronically prescribe controlled substances, as long as they use two-factor authentication credentials to do so.

Cox explains that the DEA’s initial set of rules governing EPCS were pretty tightly written and fairly secure. Those rules required practitioners to digitally sign the prescriptions and transmit them to the pharmacy. The pharmacy would then validate those digital signatures, which would give end-to-end control from the point that doctor signs the prescription to the point when the pharmacy fills it. It also ensured an electronic record of what happened.

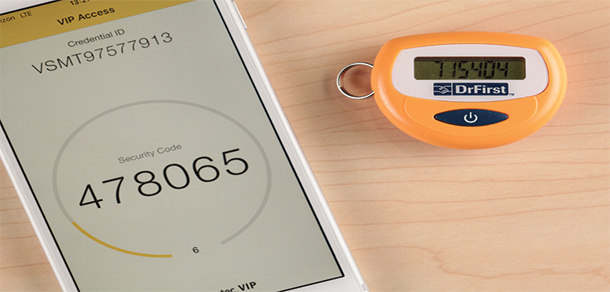

But some from the credential service provider community pushed to use other methods for authentication in addition to digital certificates, such as one-time passwords. Varying interpretations of the EPCS rule have come up since then, Cox explains. “It’s not as secure as it was originally intended,” he says.

The auditors reviewing EPCS applications are another issue, Cox believes. Each system that is being used for EPCS, whether it’s a prescribing app or a pharmacy app, has to go through an independent third-party audit. The DEA has certified a handful of auditors, but the rules allow others without that certification to perform audits. “Auditors interpret the EPCS requirements differently, which leads to inconsistencies in how applications are or are not approved,” he says.

EPCS makes it legal for doctors to electronically prescribe controlled substances, as long as they use two-factor authentication credentials

Cox says he is hopeful that the DEA will clear up some of the issues related to EPCS in its final rule, which could be released in 2016.

Requirements overwhelm doctors

Not all doctors have been eager to comply with two-factor authentication, as some find the requirements onerous.

“There’s a lot of resistance, and we need more education,” says Dr. Tom Sullivan, chief strategy and privacy officer for e-medication management software company DrFirst.

Sullivan cites a few challenges doctors face with two-factor authentication. The first and biggest one, he says, is that doctors have to go through a one-time identity verification process in order to obtain a two-factor authentication credential. “There’s reluctance on the part of doctors to go through this one-time hurdle because it costs a little extra and it takes a little time,” Sullivan says.

The most common form of identity proofing involves providing financial information, such as a credit card, which some physicians have been reluctant to provide. “We’re trying to move away from that because people don’t like to give up their credit cards.”

In response to the doctors’ concerns, Sullivan got some of his DrFirst colleagues to go to NIST’s headquarters and convince them to loosen up some of their security recommendations for EPCS.

“We said they should give a little break to health care because doctors are already so credentialed and identity proofed that it is redundant. We’re probably the most regulated industry in the world, or at least in the United States,” he says.

When working with either doctors or hospitals, Sullivan emphasizes that EPCS isn’t just a law, but also a process that can increase productivity and improve patient safety.

E-prescribing also makes it so that doctors and patients can interact over the phone, so the patient can avoid having to drive to the doctor’s office and then drop off the prescription at the pharmacy. Sullivan says that although most doctors like e-prescribing and the conveniences that come with it, they dislike the requirements involved.

“We want to change the attitude that this is just another mandate getting in the way of the efficient diagnosis and treatment of patients,” he says.

The government was insistent that it wanted to increase security, rather than simply match the security of paper-based prescriptions

Dr. Peter Kaufman, chief medical officer for DrFirst, points out that e-prescribing has several advantages. For one, a prescription is more secure when sent electronically than with a wet signature, because it’s going through a secure trusted network. “The DEA in its early stages was very insistent that they didn’t want to match the security of paper,” Kaufman says. “They wanted to increase the security.”

Perhaps the greatest advantage is that e-prescriptions allow doctors and pharmacies to check the prescription against a patient’s allergies and medical records. Kaufman cites the Institute of Medicine’s 1999 report “To Err is Human,” which linked medical errors – including prescribing issues – to as many as 98,000 hospital deaths. “E-prescribing has helped us with those issues a great deal,” he says.