02 December, 2014

category: Biometrics, Government

Dorothy Bullard, manager of marketing publications, MorphoTrak

2014 marks the 40th anniversary of Automated Fingerprint Identification Systems (AFIS). In forty short years, fingerprint matching has become a part of everyday life; from law enforcement agencies using fingerprints to solve crimes, to ordinary people using a fingerprint to unlock their smart phones, clock in at work, at the gym, or pay for cafeteria lunches.

Keep reading to find out about the history and evolution of fingerprint matching. You’ll also learn how the old adage “It’s not rocket science” doesn’t quite fit when we’re talking about fingerprint science.

Fingerprint matching: a science that is both young and old

Fingerprint patterns never change and no two fingers are alike. More than three thousand years ago, Babylonians recognized that each person’s fingerprints were unique and could serve as an identifier. We know that fingerprints were used in ancient Babylonia on clay tablets as signatures for business transactions. Fingerprints were also used in China on clay seals more than 1500 years ago.

But fingerprint analysis didn’t really become a “science” until the 1800s, with widespread use of fingerprint cards for criminal investigation and identification not becoming a reality until the early 1900s.

For more than 100 years now, the ridge formations and patterns on our fingertips have provided the best and most accurate measure of individual personal identities.

Since 1924, the FBI has been the country’s central national repository for fingerprints, which arrive by the thousands each day. It was very much a production-line type process in the early days. The prints would be classified via the “Henry” system of loops, whorls and arches that was developed in 1896.

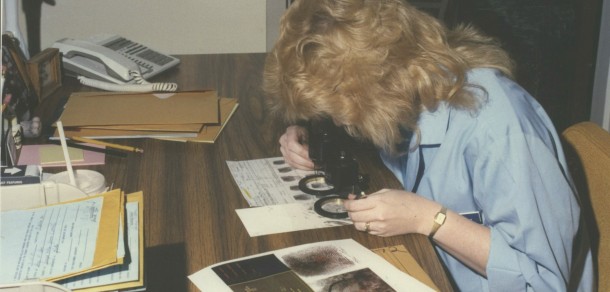

In a Henry search, the FBI’s examiners would have to find the proverbial needle in a haystack. An examiner would be led to a room of cabinets, which would lead to a specific cabinet, then to a drawer, and then maybe lead to a set of prints that had a similar classification. Using this manual comparison method, it could take several days to compare a print against perhaps a thousand other sets of likely matches. This made it difficult to solve serious crimes in a timely manner.

In a Henry search, the FBI’s examiners would have to find the proverbial needle in a haystack. An examiner would be led to a room of cabinets, which would lead to a specific cabinet, then to a drawer, and then maybe lead to a set of prints that had a similar classification. Using this manual comparison method, it could take several days to compare a print against perhaps a thousand other sets of likely matches. This made it difficult to solve serious crimes in a timely manner.

By the 1960s, the FBI’s fingerprint card collection had grown to comprise millions of cards and their manual Henry system was unmanageable. The FBI knew that automation would be the key to success in speeding up fingerprint matching. The Bureau contracted with the National Institute of Science and Technology — which at the time was called the National Bureau of Standards NBS — to study the feasibility of fingerprint automation. The bureau identified two key issues that automation would have to overcome:

- Automatically scanning and identifying minutiae, the points of comparison on a fingerprint

- Automatically comparing and matching lists of minutiae

The FBI then funded studies to address the problems of scanning and feature extraction and of matching. By 1969 the Bureau was convinced that the task could indeed be automated, and issued a request for proposals, followed by a prototype pilot test. Two systems were built, one by Rockwell Autonetics — now MorphoTrak — and another by Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory. After a thorough technical evaluation, the FBI awarded the contract to Rockwell to build five high-speed card-reading systems.