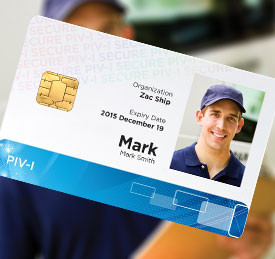

New ID standard lacks vetting of PIV, PIV-I but expands options for enterprises

29 October, 2012

category: Corporate, Digital ID, Government, Library, Smart Cards

Late last year a new acronym joined the alphabet soup that makes up the federal identity landscape when CIV, or Commercial Identity Verification, was announced.

CIV is a relative–some say a sibling while others argue a distant cousin–to the Personal Identity Verification (PIV) credential that is used by federal employees for physical and logical access to facilities and networks. PIV was mandated out of the Homeland Security Presidential Directive 12 back in 2004 and the FIPS 201 specifications that followed.

Years later, the need for contractors to access to federal buildings and networks gave rise to the Personal Identity Verification-Interoperable (PIV-I) specification. PIV-I credentials are technically interoperable with the PIV infrastructure, and issuers must comply with the identity proofing, registration and issuance policies described in FIPS 201. PIV-I cards are cross certified for PKI with the Federal Bridge to enable the contractor employees to securely access protected resources.

Commercial Identity Verification and the CIV cards are the new kid on the block. CIV leverages the PIV-I specifications, technology and data model but it does not require cross certification to the Federal Bridge. Any enterprise can create, issue and use CIV credentials according to their own requirements.

Some say CIV is a positive, necessary step and another option for enterprises to secure networks and facilities. Others, however, are adamant that credentials that use the spec cannot be trusted.

“To get very high-assurance you have to do a number of things, it’s technology and it’s policy,” says Tony Cieri, principle with Cieri Consulting.

To receive a PIV credential an individual has to go through an identity screening against a criminal database and a suitability check to make sure they can work for the federal government. This enables an individual to receive a PIV, a cryptographic token that meets the four levels of identity assurance used by the federal government. Background checks for PIV-I holders vary depending on the access level required, but these are typically level three, cryptographic tokens, Cieri says.

“If there’s PIV and PIV-I what does CIV get you?” Cieri asks. “You can be using a smart card, you can be using cryptography but you have no assurance that the person is who they claim to be. It’s the technology of PIV without the processes that go with it.”

A CIV credential is a level one token–self-asserted identity–at best level two, Cieri says. There are many other credentials that individuals can use for levels one or two assurance so he questions why an organization would go to the expense of issuing a cryptographic token.

PIV-I credentials have the ability to be provisioned to work on government networks, Cieri says. There is uncertainty regarding this type of use for CIV credentials, because the credential holder has not been vetted. “Why would you trust it?” Cieri asks.

The cost associated with CIV would be similar to that with issuing a PIV-I credential so it makes more sense to issue the credential with more assurance around the identity, Cieri says. “If the cost is commiserate go a step further and go with PIV-I,” he adds.

Cost is what it may all come down to, says Peter Catteneo, vice president at Intercede Ltd. CIV credentials, because they wouldn’t be cross-certified with the federal bridge, would be less expensive because providers wouldn’t have to go through that process.

Other than cost it is simply a policy difference between CIV and PIV-I, Catteneo says. “PIV-I comes with well defined policy requirements and for some people those polices meet their business requirements,” he explains. “CIV provides a way to create cards that are technically interoperable but express different policies.”

Intercede has deployed CIV credentials in different enterprise environments, Catteneo says. Those organizations wanted to use a standardized technology credential that would only be used within that environment. For that purpose, cross certification and in-depth identity vetting weren’t important.

“There are two dimensions to authentication, one is how strong is the background check and the other is how strong is the authentication tool being presented,” Catteneo says

For a closed enterprise environment a CIV credential is an alternative, he says. “PIV did a good job with identity enrollment for federal employees and PIV-I leveraged that for non-federal employees,” he adds. “But there are some industries that want high-assurance credentials but don’t want to follow the PIV validation processes.”

While trust with a CIV credential may be an issue outside of the issuer’s network, if it’s never used outside the network it is not a problem, Catteneo says. “The intention of PIV and PIV-I are to be part of one ecosystem,” he says. “They CIV may not be part of the same ecosystem.”

CIV gives an enterprise options when looking for credentialing technology, Catteneo explains. In the past enterprises had to go with vendor specific applets, but CIV uses a standardized card body and data structure so end users aren’t locked into one vendor.

So which specification should an organization choose? It comes down to how the credential will be used. If it’s for an internal network, CIV may be the right choice. But if trust is required outside the enterprise another option may be necessary.